This Business Is a Lemon, and a Family Wants to Keep It That Way

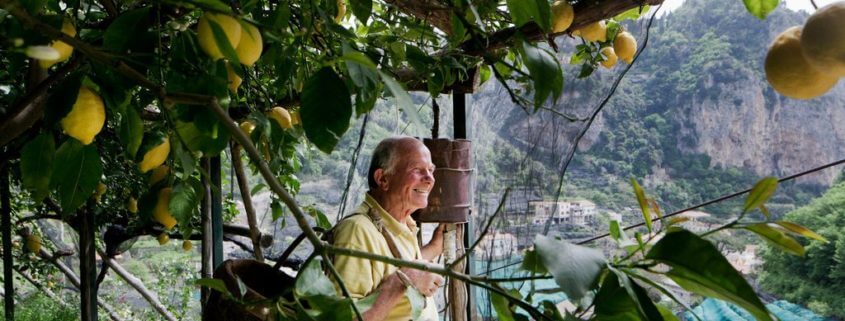

AMALFI, Italy — On a recent spring morning, Luigi Aceto, a hale 78, climbed a ladder in a terraced lemon grove that stretched up the hillside in one of Italy’s most picturesque towns and expertly began snipping lemons into a wicker basket. The sun was shining. The lemons were ripe and as big as fists. The scent of blossoms was intoxicating.

Mr. Aceto, nicknamed Gigino, was born and raised in these lemon groves, where his family has been working for centuries, first as tenant farmers, then as landowners. But with the land on the Amalfi Coast far more valuable today for luxury tourism than boutique lemons, Mr. Aceto worries what the future will bring.

“I have the honor and the burden of bearing witness here to six generations,” he said contemplatively, as he stood on a promontory in the lemon grove, wearing, as it happens, a lemon yellow shirt. He was referring to the three generations that preceded him as well as his own, and those of his two sons and grandchildren.

In many ways, the Aceto family tree mirrors Italy’s transformation from an agrarian peasant society before World War II into an industrial power afterward — and its lingering ambivalence about whether it wants to compete globally or believes its future lies in local traditions. The debate has become more intense since the introduction of the euro in 2002, which raised the price of Italian exports, making it harder for small businesses to compete.

Today, 90 percent of Italian businesses have fewer than 15 employees. The Acetos make a niche product — world-famous lemons, prized for their low acidity and delicate flavor — and like many small Italian businesses, they are reluctant to grow, preferring quality over quantity, tradition over expansion. Mr. Aceto wants the lemon groves and the business to stay in the family.

Credit :The New York Times

“My two sons work for the business and are dedicated; I count on them,” he said.

Mr. Aceto’s son Marco runs the production side of the company, La Valle dei Mulini, making limoncello liquor, lemon honey and other products from the lemons, which are so sweet you can eat them whole. Marco’s wife works in the family shop selling the products in the town’s touristy main square. Mr. Aceto’s other son, Salvatore, recently left a job as an accountant to come back to work for the family business.

That isn’t always the case for other nearby families, whose children left the lemon groves to go to college and seek professional jobs in the cities. Keeping the lemon groves alive is a constant struggle.

“One of our main goals is to prevent the abandonment of the gardens on the coast,” said Salvatore De Riso, a well-known pastry chef and the president of the Consortium for the Protection of the Amalfi Lemon. “So many have been abandoned, and we’re trying to get them back by involving the owners. We’d like to valorize the Amalfi lemon, which is unique in the world.”

Mr. De Riso said that the consortium, which certifies the quality of lemons in products like limoncello to protect them from low-quality imitations, is trying to help local producers raise production.

The consortium is also trying to get state financing to help the boutique producers stay afloat. But that is a vexed issue in Italy, where in past years, although generally not in Amalfi, the misuse of European Union agricultural subsidies has often made it more lucrative for larger farms to let fruit rot on the tree than to pay the costs of harvesting and transporting it.

Although Mr. Aceto helped start the lemon consortium, he no longer wants to be part of it, saying it is pushing small growers like him to produce too much.

Mr. Aceto would also like to sell the lemons himself, and frowns on what he calls “mercenaries,” or wholesalers who buy lemons from small producers and sell them at a markup to larger distributors.

Mr. De Riso disagrees. He said that increasing the quantity of production would help small producers earn more without detracting from the quality. All lemons certified from Amalfi must be of the “sfusato” family, which comes from the Italian word for spindle, because of their pointed ends. These grow only in the microclimate of the Amalfi Coast, where cooling breezes are trapped between steep mountain valleys.

The lemons were first brought to the Amalfi Coast centuries ago on trade routes from the Middle East and were treasured by sailors for warding off scurvy and other ailments at sea.

For the Aceto family, the euro — and the euro crisis — is yet another phase in a long and rich history. Gigino Aceto’s great-grandfather, grandfather and father tended the lemon trees for a local nobleman, when the Italian south had a largely feudal economy. His father was able to buy some land when a local noble family needed an infusion of cash.

The family’s limoncello. CreditGianni Cipriano for The New York Times

Mr. Aceto was born in 1934, the eighth of 13 children; his parents got a special large-family subsidy from Mussolini’s Fascist government. In 1968, he enlarged the plot to about 20 acres with a special 40-year loan from the Italian state at 1 percent interest, part of an agrarian reform aimed at helping farmers buy their own land.

He isn’t nostalgic for the past and still remembers being a child during the war, when the family nearly starved and he and his siblings were sent to gather herbs and anything else edible. “We had relatives in America who sent us packages,” Mr. Aceto recalled. “Now China is taking over. That’s how the times are going.”

Faced with global competition, Mr. Aceto’s son Salvatore is not convinced that the euro is helping small businesses like his. “I’d say no,” he said. “There are lots of positive sides, but the other side of the coin is that we didn’t benefit enough. If we still had the lire, we’d have stayed more competitive as agricultural producers.”

The Aceto lemon groves could be sold for millions of euros for luxury vacation properties, but the family will hear none of it.

“I’m taking care of the patrimony of humanity,” Gigino Aceto said. Planted in a series of stonewalled terraces, the roots of the lemon trees help prevent soil erosion and landslides, a growing problem with the torrential rains of recent years. “The rays of the sun penetrate under the roots, so that the lemon is like a little baby in its cradle,” he said.

“Maybe lemon juice runs in my veins instead of blood,” he added.

After his afternoon nap, Mr. Aceto showed off the family’s smaller plot, high on the hills above the coast. A sweet breeze blew through the lemon grove. The sounds of traffic and water lapping on the shore rose from below. Above were the steep stone walls of the local cemetery. Salvatore Aceto looked up. “Here, even the dead are in paradise,” he said.